Lincoln: The New Capital

In 1859, a handful of settlers met on the banks of Salt Creek to organize Lancaster County in the Territory of Nebraska. As the county seat, they selected a grassy plain on the east bank of the creek, about a mile southeast of a natural salt basin. The county's founders believed that a profitable industry collecting salt could be developed there, but they were proven wrong. Instead, the future of Lancaster, the little hamlet which had "no original reason for existence," lay in the political squabbles over the location of the state capital for Nebraska, admitted to statehood in 1867. Following protracted and fierce debate in the Legislature, a Capital Commission was empowered to select the location. In July 1867, the commission met in Captain Donovan's cabin near what is now 9th and Q Streets and voted to make Lancaster, renamed Lincoln, the Nebraska capital.

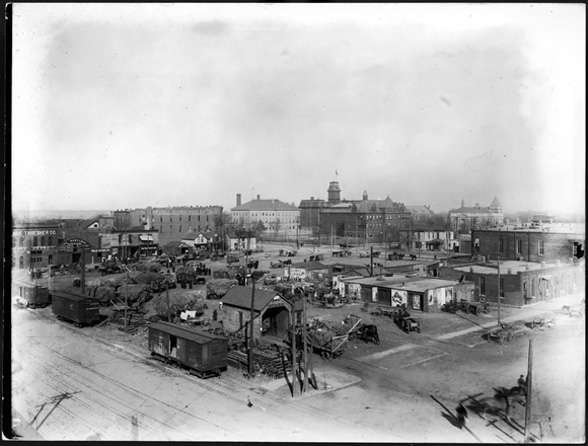

View north from O Street of Burlington & Missouri River Railroad yard, ca. 1873. Courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society.

The Why and How of the Haymarket

The "Haymarket" name can be traced to Lincoln's first decade. In the original plat of Lincoln of 1867, a "Market Square" was designated between O and P Streets from 9th to 10th. That square was an open-air market for produce and livestock, as well as a camping ground for immigrants and a general gathering place. Wagons and animals thronged Market Square, along with land sharks, tin-horn gamblers, and the other denizens of a pioneer town.

When the federal government was persuaded to erect a post office and courthouse in Lincoln in 1874, the city and state donated the original "Market Square" and moved its functions two blocks north, creating "Haymarket Square" bounded by 9th and 10th, Q and R Streets. Scales were provided for weighing hay, cattle, and produce. Haymarket Square continued "to provide space for the teams and wagons of country folk, a mart for hay, and a camping ground" well into the 1880s. It became the location for the first City Hall from 1886 until 1906. Today it is home to the Lincoln Journal Star’s printing plant and distribution facility.

The Haymarket name survives in the historic warehouse district immediately west of the old Haymarket Square. The Lincoln City Council designated the eight-block Haymarket Landmark District in 1982, giving it recognition and protection as a major element of Lincoln's heritage. The National Park Service subsequently certified the Haymarket as the equivalent of a district listed on the National Register of Historic Places, with the protection and privileges of that status.

The City adopted a redevelopment plan for the area in 1984. The plan called for the revitalization of the Haymarket through public infrastructure improvements and private rehabilitation projects, to provide a mix of uses including offices, retail stores, entertainment establishments, and residences. In 1985 the Haymarket was selected as a demonstration project by the National Main Street Center. The Haymarket was the first urban warehouse district to undertake that highly successful economic revitalization program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In the decades that followed, project by project, business by business, with new infrastructure and special events like Farmers Market, the Haymarket has been transformed from a largely vacant, crumbling area into a vibrant part of Downtown Lincoln. It is a special place to live and work, to create and recreate. The Haymarket’s success was recognized by the American Planning Association in 2009 with its “Great American Neighborhood” designation. In 2014 the area was listed on the National Register as Lincoln Haymarket Historic District by the National Park Service.

Wholesale Houses

In Lincoln's first years, the area we call the "Haymarket" was a place of small houses and retail stores. As the town grew, and especially as it succeeded in the 1870s and '80s in attracting railroads to the Salt Creek bottom lands, wholesale jobbing and manufacturing businesses began displacing the stores and houses east of the rail yards. Today, several large warehouses remain in that area that reflect Lincoln's boom-town decade of the 1880s, when the population quadrupled from just over 13,000 to more than 55,000. The Haymarket district's few, smaller buildings of the 1890s correspond to a time of nationwide depression, matched by a decline in Lincoln's population to about 40,000 by 1900. The ensuing twenty years were the Haymarket's principal period of construction, matching Lincoln's steady growth back to the 55,000 level of population by 1920.

The "wholesale jobber" of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the new middleman in the distribution of goods. Rather than selling goods owned by others and earning his living on a commission basis, the jobber purchased goods from manufacturers and utilized traveling salesmen to sell directly to retailers. Manufacturers could concentrate on supplying a relatively small number of jobbers, rather than marketing (and extending credit) to hundreds of shopkeepers. Retailers could deal with traveling salesmen, rather than searching out their own suppliers. And the jobber, by holding title to the merchandise, took a greater risk than the commission merchant and had a greater opportunity for profit. The number of salesmen and the size of the sales territory were sources of pride to wholesale firms and were almost always included in their promotions. "Today [1923] the Western Glass & Paint Company does a large wholesale business in 8 states through a staff of 9 traveling salesmen." By 1904 Lincoln's market region included not only all of Nebraska, but the Black Hills of South Dakota and portions of Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, Kansas, New Mexico and Utah. Only Omaha, with its river port and rail hub, boasted a larger jobbing trade in Nebraska.

The jobbing trade had three hallmark building types: hotels for the traveling salesmen, warehouses for the merchandise, and railroad depots and train yards for shipment. The Haymarket retains two old hotel buildings (both on 7th Street, see buildings #6 and 7, below) of the dozen or so that operated at various dates. Modern hotels at the east, west, and north edges of the district are also reminders of this tradition. Lincoln Station, the Burlington Railroad depot which anchors the west side of the district and the 8th Street loading docks recall the Haymarket's rail transportation lifeline. Most of all, a dozen substantial warehouses reflect one of early Lincoln's most vital commercial activities.